Though it has to have been quite recently, I don’t remember when I first heard of the Kowloon Walled City. But it was a place custom-made to capture the imagination. Mine, anyway.

Demolished by the Hong Kong government in 1993-4, the Kowloon Walled City was a collection of some 350 buildings constructed on a couple city blocks’ worth of land in Kowloon near the now-defunct Kai Tak airport. Though it began as a military fort, it grew in recent times into a dense community, a kind of city within a city that, legend had it, existed off the grid, outside regular law and order. At the end, at least, the City was said to be controlled by the Chinese organized crime syndicates known as the Triads (though like many legends of the Walled City this is now disputed). With an official population of 33,000 residents (some estimates put the number as high as 50,000), the Walled City notoriously sported the highest population density on Earth (extrapolated, some 3.2 million people per square mile; that’s considerably denser than the tenements of New York’s Lower East Side, previously thought to take the prize).

I first flew into Hong Kong when I came to the MD-11 in 2009 or so. The Walled City was long gone by then, but in historical terms I feel like I just missed it. From my first visit to this place I was taken by the grimy back streets and chaotic, ramshackle construction (as my tedious - photos - attest), and in truth there’s a lot of Hong Kong that looks very similar to pictures of the Walled City (our old hotel on Nathan Road is right next to a similar conglomeration of buildings called the Chungking Mansions—I’d never heard of that place either until researching the KWC). There’s a lot of crumbling masonry construction here, and many old residential buildings seem to be kept going by improvised repairs. By our standards, many seem on the verge of collapse, or at least well on their way. So it’s not the construction of the Walled City itself that is odd: it’s how tightly packed it was. You might say the Walled City was Hong Kong only more so. The pictures remind one of the city of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, incredibly dense and dark and wet and tangled.

The Wikipedia article details some of the history of this plot of land, and though there was a residential presence for much of the last 80 years most of the construction that housed such a density of people dated from the 1960s-80s. Though Hong Kong was ruled by the British, the Walled City was exempt, an area still under Chinese control. At the end of WWII, Chinese squatters flocked into the City under Chinese protection. The British tried to dislodge them, but eventually washed their hands of the place. Keeping order there was more trouble than was deemed worthwhile. This situation—governance by in-absentia Chinese, and abandonment by the Brits—allowed the drugs and gambling and prostitution businesses to grow unchecked. It also meant that nobody was governing the construction process as more and more buildings were erected (though, interestingly, Wikipedia says that the proximity of the Walled City to the Kai Tak airport meant that no buildings could be built above 14 stories in height; I wonder who agreed to and enforced that rule?). Structures were built wherever they could be made to fit.

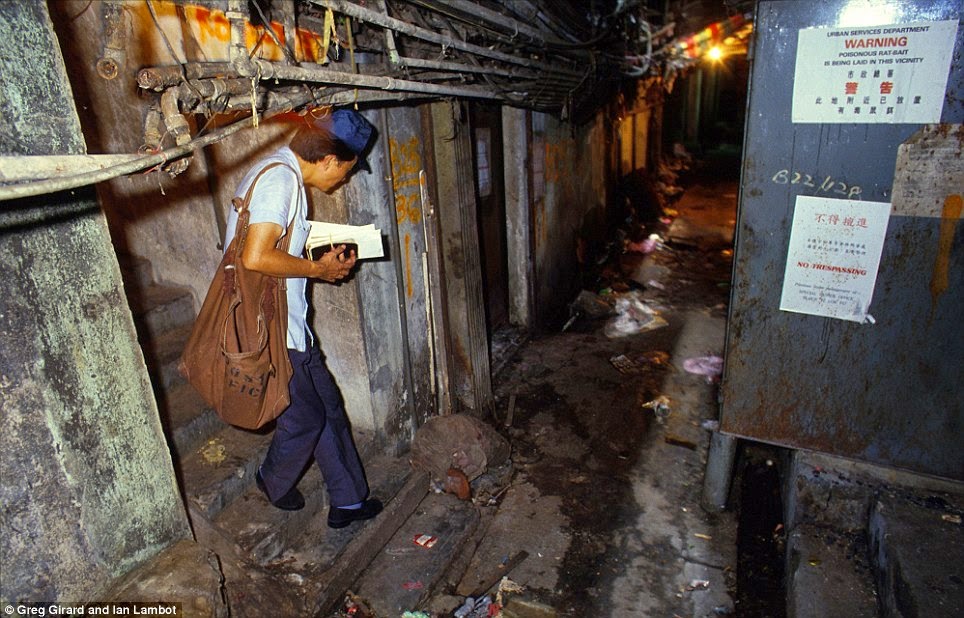

Yet the vice and mayhem existed cheek-by-jowl with pensioners and thousands of families, all crammed into tiny spaces (the article says most apartments were only 250 square feet). It became very nearly a self-contained ecosystem, as most everything a person wanted or needed could be had within the City's walls. Numerous unlicensed doctors and dentists operated there--that is, medical professionals who wanted to avoid the exorbitant licensing fees of Hong Kong (a unique subculture that would be a fascinating study in and of itself) and there were many restaurants and a motley assortment of schools and daycares. There was mail service, though very few people were able to navigate the compound in any comprehensive way (I love the story of the old woman who lived there for years but said she never went anywhere but directly to and from her residence, so she didn’t know the rest of the place at all). Though it seems that several water mains were eventually routed to the City, there were no regular utility services since the city was not involved in the construction. And yet the residents seem to have cobbled together utilities, as the many pictures of bakeries and small factories and tiny apartments with a tap and bare light bulbs attest. But in most cases ad hoc means improvised: pictures show an unruly tangle of wires and pipes and hoses in all the alleyways, many of which leaked so that the dark passages were frequently damp. The alleyways themselves were originally open passages between buildings, but most of them were covered and structures built atop them, so that there were hundreds of internal passageways known only to the residents of each particular section. The rooftops were public outdoor spaces, frequently used by children and by the residents of the upper floors.

I’ve taken pictures in Shanghai of an old part of the city that reminds me of the Walled City, but without the verticality. Many of the structures in this part of Shanghai look to be uninhabitable, and yet clean and smartly-dressed people can be seen incongruously issuing from them. And so it must have been with the Walled City: thousands of children were raised there, leaving their residences inside the walls to walk to school like all other kids. It’s the juxtaposition of these extremes—normal family life next to brothels and drug dens and cookie factories and Chinese bakeries and illegal doctors, all piled on top of each other in incredible density—that the pictures bring home to you. Pictures do so much better than words here. The photos of the exterior show a chaos of birdcage balconies and rooftop porches and a forest of antennas, all crammed together higgledy-piggledy without adhering to any master plan.

At least in theory—setting aside the whole organized crime angle, which would be quite beyond my ken—I would give my eye teeth to explore such a place. Well, there exists the next best thing: I learned that a book of photographs and stories about the Walled City by Britons Greg Girard and Ian Lambot had been published around the time of the City’s destruction. The stories of the people who lived here and the small factories that operated here, all under the radar, in the midst of one of Asia’s premier and most bustling and cosmopolitan cities is one of those stranger-than-fiction things. The book—City of Darkness—is out of print and the few copies available on Amazon were asking some $900. But as luck would have it, the authors are producing a 20-year anniversary edition with substantial updates—City of Darkness Revisited. The reissue project was funded by a successful Kickstarter campaign, and though I missed the campaign I was thrilled to find that I could pre-order the new book from London. Deliveries are expected in September.

I went through a period where I was infatuated with the Kai Tak airport. It was another of those places that could only have existed here, an incredibly busy one-runway airport in one of the world’s densest and most vibrant cities, an airport built on created land which required huge jets to fly very close to—and in some cases below—the skyline of the city. (Do a search on YouTube sometime for “Kai Tak” and you’ll see some spectacular airplane footage.) The spit of land is still readily visible jutting out into Victoria Harbour, now converted to a cruise ship dock and terminal. The Walled City was situated right off the end of the runway, and much of the footage of airplanes scarily close to buildings was doubtless taken from the rooftops of the Walled City, jumbo jets passing in a steep bank, so close you could read the writing on the fuselage. (Many of our pilots have stories of flying in and out of Kai Tak, though it was closed by the time I got hired here.)

About a year ago I walked the five or six miles from our hotel in Tsim Sha Tsui over to look at the remains of Kai Tak (alas, not being able to see much). At that time I had not yet heard of the Walled City, or I would certainly have looked for its remains. Though the Walled City is gone, the city of Hong Kong put up a park on the exact footprint of the old Walled City, called, appropriately enough, the Kowloon Walled City Park. That was the destination for today’s walk. Only a few artifacts remain of the settlement. Several of the entry gates are still there, and there are maps and diagrams throughout the park showing the former locations of things. But knowing it was here is a far cry from seeing it in person. My loss, but luckily a good record of the place exists.

(In addition to Wikipedia, much of this information--and most of the photos--come from Greg Girard and Ian Lambot via their website, and from a Daily Mail newspaper story using the same source.)

6 comments:

Great video footage here:

http://youtu.be/dj_8ucS3lMY

And here:

http://youtu.be/Lby9P3ms11w

Wow. Looks like something out of Bladerunner....

A great infographic here:

http://kickassfacts.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/City-of-Anarchy.jpg

I may have to read the book after your done with it. Very interesting place. I noticed in one pic that there is a plane taking off seemingly right next to the building. Where did they take the dead? And where did the gray water go etc.? I'm sure the book tells all.

One of the many rumors, it seems, is that the place was totally lawless. I see on the website that the authors say it wasn't nearly as true as claimed. The rumor was that the police would never enter except very exceptionally and in large numbers, but the authors say that's untrue; there were daily police patrols with pairs of cops.

And yet there WERE a lot of brothels and drug dens and places to gamble. So there's at least a kernel of truth. I suspect dead bodies were carted outside by the people who lived there, and then processed like dead people everywhere else in Kowloon. It'll be interesting to see what the book says.

Not sure about gray water, but I'd bet there were pipes put in that routed everything to the storm drains. There were supposedly a bunch of wells dug on the property before it got built up, but the city eventually routed four standpipes to just outside the entrances so people could get water. But it still often had to get carried up.

Fascinating. I'm just mesmerized by this place!

Post a Comment