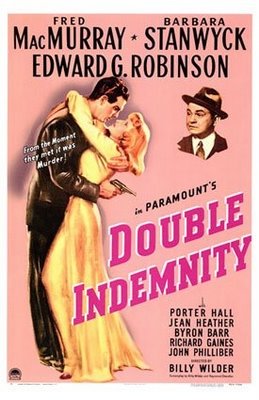

I've been watching the special edition of Double Indemnity, the seminal 1944 Billy Wilder noir film about insurance fraud and murder.

I'm not very comprehensive in my knowledge of film noir, but I know what I like and I figured out a decade ago that I rarely see one without being taken in by the dark subject matter and fabulous visual style. Robert Osborne in his introduction cites Double Indemnity as the official beginning of the film noir movement (a movement which was not identified as such until some 20 years later), and one of the movement's best. In fact, it's a fantastic film regardless of genre. It's perfectly cast, wonderfully paced, and visually innovative. And the story is compelling with minimal adjustment to period.

I made it through high school and into college before I really paid any attention to the visual aspects of anything. And now, having blinkingly discovered this side of life as an adult, I'm more attached than I might otherwise be. I love looking at the world as it used to be, the gritty depiction of the America of my grandparents' youth. This is a world where the fresh-scrubbed picture of society from the WW2 propaganda pictures comes crashing down, a world where people are weak and life is harsh. No spin doctors here. Hotels have their own detectives. Nobody seems to like daylight. Everyone smokes and drinks and cheats on their spouse. It's always raining.

Color was newly available to movie makers in 1944, but with Double Indemnity black and white was conscientiously chosen and made a character in the movie. In what became a pattern for noir films, much of the action occurs at night and everything takes place obscured by deep shadow and in a haze of cigarette smoke. The main noir character is often a man at odds with society, someone misunderstood and often feared or despised. The story is told from the point of view of the criminal; the movie's whole perspective is that of the criminal element--we are practically encouraged to root for the anti-social. Fred MacMurray's character, insurance agent Walter Neff, is generally sympathetic--moreso than with many noir characters--but Barbara Stanwyck more than makes up for it. In any case, we have a front row seat for a series of bad decisions which result in his seemingly-inevitable slide to the dark side.

For those not already familiar with the story, Barbara Stanwyck is married to a stuffy oil executive, and decides, with a little help, to make sure his accident insurance is in order and then have him knocked off for a big payday (this story--adulterers committing murder for money!--while it may sound commonplace in 2006, is a steel toe to the groin of polite, churchgoing 1944 society). The help comes in the form of the cast-against-type MacMurray, who is lured as they always are to the femme fatale, and to his stumbling downfall. Is it love? Infatuation? Hubris? The thrill of the chase? Walter Neff dabbles in all these things, and is convinced that, being an insurance man himself, he can perfectly fool the system. But the deception is smelled out by Claims Manager Barton Keyes, who is a close personal friend and coworker of Neff. And, of course, nothing ends up being quite what it seems initially, and worlds collide. It's cat and mouse, with a bit of detective intrigue thrown in.

It's the relationship between Walter Neff and Barton Keyes that really makes the movie, and indeed the role of Barton Keyes was juicy enough to lure headliner Edward G. Robinson to accept a supporting part. This is, in an unorthodox fashion, the love center of the movie. They're not lovers, of course, but only close friends; but without this source of warmth, we could not gauge Neff's fall nor the icy emptiness of Phyllis Dietrichson. Barton Keyes is a blustering, cranky bully, and yet Robinson manages to play him with great subtlety and absolute conviction and it's a thrill to watch. Barbara Stanwyck was also at the top of her game--she is cited by one of the film historians in the DVD's special features as perhaps Hollywood's greatest actress of all time--and this polish and confidence is played against Fred MacMurray, who was still relatively unknown and a man personally opposed to playing so unsavory a character. MacMurray's essential goodness plays well here, and makes his slide a bit awkward and more believable.

It takes the older movies--movies which were so much a product of the restrictive production codes of the time--to show us how badly our modern action flicks miss the mark. Hollywood so often fails utterly to grasp the concept that less can be much, much more. This movie is all about the story--not about the size of the explosions or the body count. It's about temptation and inner conflict; it's about the dark corners of the human psyche and the frailty of human will. The whole story is about the anticipation of what might happen, and our hope that the inevitable might be averted. This is a movie which I would strap Jerry Bruckheimer down and force him to watch again and again until some sense of subtlety and aesthetic sophistication oozed osmotically into his over-caffeinated, television-raised psyche.

I give this one an A+

2 comments:

I decided, after taking my SECOND film class (I really like A's) that the category "Film Noir" should include all movies by Eddie Murphy, SAmuel L Jackson, and Lawrence Fishbourne.

Bah Dum Bump.

A terrific post -- I enjoyed your comments immensely!

http://relativeesoterica.blogspot.com/2006/12/all-of-those-things-and-more.html

http://relativeesoterica.blogspot.com/2006/11/jazz-noir_116251878908288967.html

Post a Comment